ON SEMELPARITY

Once, I worked in an office with two children — daughters of my coworker, six and eight years old. They were homeschooled and lived on a farm in the middle of nowhere. They were gentle and polite girls with big, kind hearts, but they were also delightful little wild things that climbed trees and ran through dewberry brambles barefoot.

One day, they brought in a empty plastic clamshell box of spring mix that contained a Superb Green Cicada, stuporous with impending death, they had found sitting in the bed of their father’s truck. They declared him their pet, and he was named Grassy. For a while, they played house with him under a desk; then, later, I heard the sound of stifled giggling behind me and felt tiny chitonous legs grip on to the back of my dress. I have more than a healthy tolerance for bugs, so I laughed and said, “Excuse me! Did you just put a cicada on my back?” and they were delighted in their mischief. My immediate thought was, thank god it was me and not someone else!

As I write, I look out over the trees below our bedroom window where once again it is summer and hundreds of unseen cicadas are screaming. They are hidden in the oaks, in the osage orange, and in all the willow trees. We don’t find any of their discarded sheds around our apartment, but the long green corpses of the cicadas still show up in the stairwell, where the creatures have gone to hiss and thrash around until they stop moving forever.

Their bodies are perfect, whole and intact, their end of life brought not by predation or disease but simply by end of purpose. They have emerged from the ground. They have shed their skins. They have scaled the trees and screamed for days upon days. They have found mates and fucked dispassionately. And then, when the mating is done, they fall to the ground and die.

This concept is fascinating to me, partly for how foreign it is to our human experience: a life cycle with a death preprogrammed for maximum efficiency. In biology, this single-reproduction life cycle is known as semelparity—nature’s tidy way of allocating resources to organisms able to healthily reproduce. Semelparity is extremely common in insects but nearly nonexistent among vertebrates. Perhaps that’s why the life of a salmon seems particularly gruesome.

What other bony animals do we know that begin to waste away and die as soon as they mate? For most salmon species, a salmon that has migrated back to its natal stream, with every last reserve of its energy depleted, will live for no more than two weeks after it arrives back home.

I have to wonder what the salmon must think, if they think of anything. In the ocean, when they are smooth and silver, do they know the horrible bulbous creature they will become? When they travel upriver back to where they hatched, do they feel nostalgia? Familiarity? When they battle for dominance for redds in the cloudy water, do they know that their bodies are already beginning to fail? Do salmon know that death is encoded in their immune system, and are they afraid?

And yet, unlike humans, salmon have clearly delineated purpose in life and death, with a usefulness that far exceeds the expectations of their biomass. Seeing the bigger picture of salmon death is a kind of beauty. Roe is a vital food source for freshwater fish like bluegill and catfish. The salmon smolt, in their saltwater phase, feed orcas and seals. Those lost on the journey upstream become the meals of otters, eagles, and bears. The wasting post-spawn bodies decompose and become nourishment for the surrounding riparian plants and trees. And, for the Coast Salish and Inuit peoples, the return of the salmon to the river runs is the return of an irreplaceable food source deeply woven into culture and story. The salmon is the hand that feeds everyone in the watershed, from river to estuary to sea.

Is there a kind of comfort in knowing that your death has a direct and necessary purpose? For humans, a meaningful death is a concept that can feel contradictory. To us, death is the great meaningless loss. Death means deprivation—a permanent absence where someone we loved once lived.

In my spiritual practice, I have begun to revisit and rethink what death gives us. When I aim to decenter myself, my phobias and feelings–I can see that human beings are not exempt from the larger mechanisms of nature and its cycles. As all living things are born, so do all living things die, and the organic matter they leave behind continues to give life to the green world. Dying is as natural as living. I choose to believe that the atoms of us, the flow of our life energy, lives on in the streams and in the trees, the insects and the fish, the birds that fly overhead.

So, too, does the essence of our life carry on in the people and places that knew us. The stories we tell, the jokes, the mannerisms, the food we prepare, the figures of speech we use, the lessons we teach in loving ourselves and others–these do not disappear when we die. I smile with my grandfather’s smile. I read my grandmother’s books. And in this way, the dead give away their lifeways to be used by the living, much in the way they give their bodies for the use of the earth.

MEDIA STUDIES

Video / Tales from the Green Valley

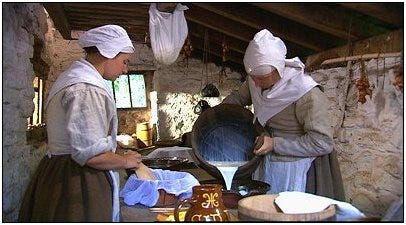

My friend Charis introduced me to this delightful docuseries on YouTube. Filmed in 2005, Tales from the Green Valley chronicles a year in the life of a team of British archeologists who set out to operate a defunct farm from the 1620s, dressed in period clothing and using only the technologies of the early 17th century.

Sowing wheat! Baking bread in a stone oven! Thatching a cow shed! Harvesting pears for the winter! If you love watching cold people in woolens cheerfully perform grueling domestic tasks, Tales from the Green Valley is for you.

Each episode covers one month on the farm, and it is fascinating to see that the team can only succeed when they act in harmony with the needs of each season as it comes. I just know that when the weather starts to get cold, I’ll be returning to the fall episodes for that nice cozy autumnal feeling. I love that it is firmly situated as a docuseries as opposed to a reality series, so the team’s struggles are never sensationalized for drama. And because they’re all archeologists, they’re all a bunch of fucking nerds who are absolutely thrilled to tell you how thatched roofs work.

Now listen. I am not stupid enough to say that I want to throw it all away and spend my life spit-roasting lambs and picking rosehips and mending stockings. Except that I am that stupid, and I do wanna do that.

Be warned: this series does not shy away from the details of dressing animals for meat after slaughter, with the blood and guts that entails. Proceed with care.

Multimedia / Emergence Magazine, “Chasing Cicadas” (Anisa George)

listen on Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts OR read the essay

During that particularly dejected year, the cicada emergence began to take on a mythic dimension for me. […] I knew, rationally speaking, that the cicadas had been performing these emergences for millions of years. I knew they wouldn’t adjust their schedule because we were dying by the millions up here. Nevertheless, to me, their imminent arrival seemed proof that we, too, could make it out alive.

In this personal essay, Anisa George reflects on the emergence of periodical cicadas and the mystery of their instinctive timing. While George recounts her own story of leaving behind her family’s Bahá’í faith, the Brood X cicadas impart lessons on the joy and the danger of the journey to emerge, transform, and become.

ON THE TABLE

Squash pancakes (Hobakjeon)

Anyone who has been to the Treehouse lately knows that Parker and I really enjoy Korean food. New to us, though, is Korean savory pancakes. Parker is a huge fan of Maangchi’s recipes and uses Maangchi’s Big Book of Korean Cooking to make us really, really good zucchini pancakes.

In the height of summer, zucchini are abundant, and you don’t need much else to make them! Hobakjeon are chewy on the inside with a light, beer-battery crunch on the outside. You share from a single plate. We served ours with a tangy dipping sauce alongside rice drizzled with sesame oil, kimchi, and oi-muchim. Got damn. It’s good.

This reminded me of something Terry Pratchett wrote in 'Reaper Man': “No one is finally dead until the ripples they cause in the world die away, until the clock wound up winds down, until the wine she made has finished its ferment, until the crop they planted is harvested. The span of someone’s life is only the core of their actual existence.”